Afterthought, comment and memories on my second solo

I HAVE NOT started in earnest to sell what I have produced; I am still figuring out what this art ecosystem is all about; its stakeholders, and their roles and interests – as lover and appreciator of artforms, as investor and auctioneer, as critic and student, and as people who cooperate to create forms and exhibitions within it, and so on. It continues to intrigue me.

In this posting, I would like to focus my thoughts diversely on the following: (1) Curator (2) Photography as art (3) My friend Khoo Boo Teik’s delivery at the reception of my exhibition which speaks volumes about memories and (4) Photographs of visitors to my second solo exhibition, “Our Legacy: Landmark Memories of Penang Free School” at The Old Frees’ Association, Sept 28-Oct 3, 2023 (read here).

Curator. This is a most misused word, these days at least. Any organiser of an event that showcases something claims to be one. As a person who has spent a better part of his life in publishing, I am acquainted with many of the processes that go into an exhibition i.e. we consider the purpose of the project, analyse its target audience, define the media of communication, craft suitable designs, choose a venue, etc, and combine the elements in a holistic manner that engages the people we wish to communicate with.

In art curation, nuances make a great difference. For my second solo, Stephen Menon gladly agreed to be my curator. After sitting with him for a couple of sessions and communicating frequently over a few months, I began to form a better idea of what art curation means. I can discern two differences:

First, we are dealing with an individual’s creation and, therefore, the curator must fully understand the artist – his creative intent, what emotions he is trying to convey, his main audience, etc – before he can advise him, before he can help him integrate the show into a whole and enhance its impact. Stephen has spent as long as a couple of years curating for young artists. Second, everything that emanates from the process should have a common underlying identity with an “artistic” twist – from the leaflet to the framing and packaging of the art, from the gallery layout for the exhibition to any ensuing publication. In other words, every element should be treated as art.

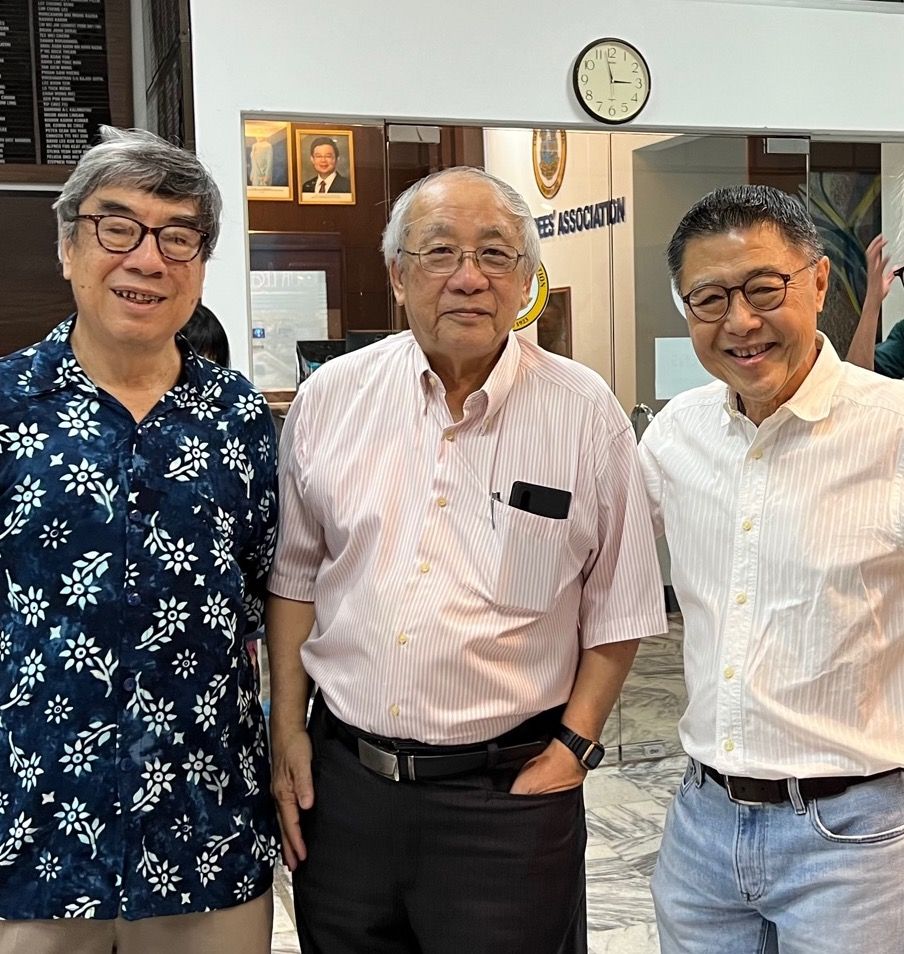

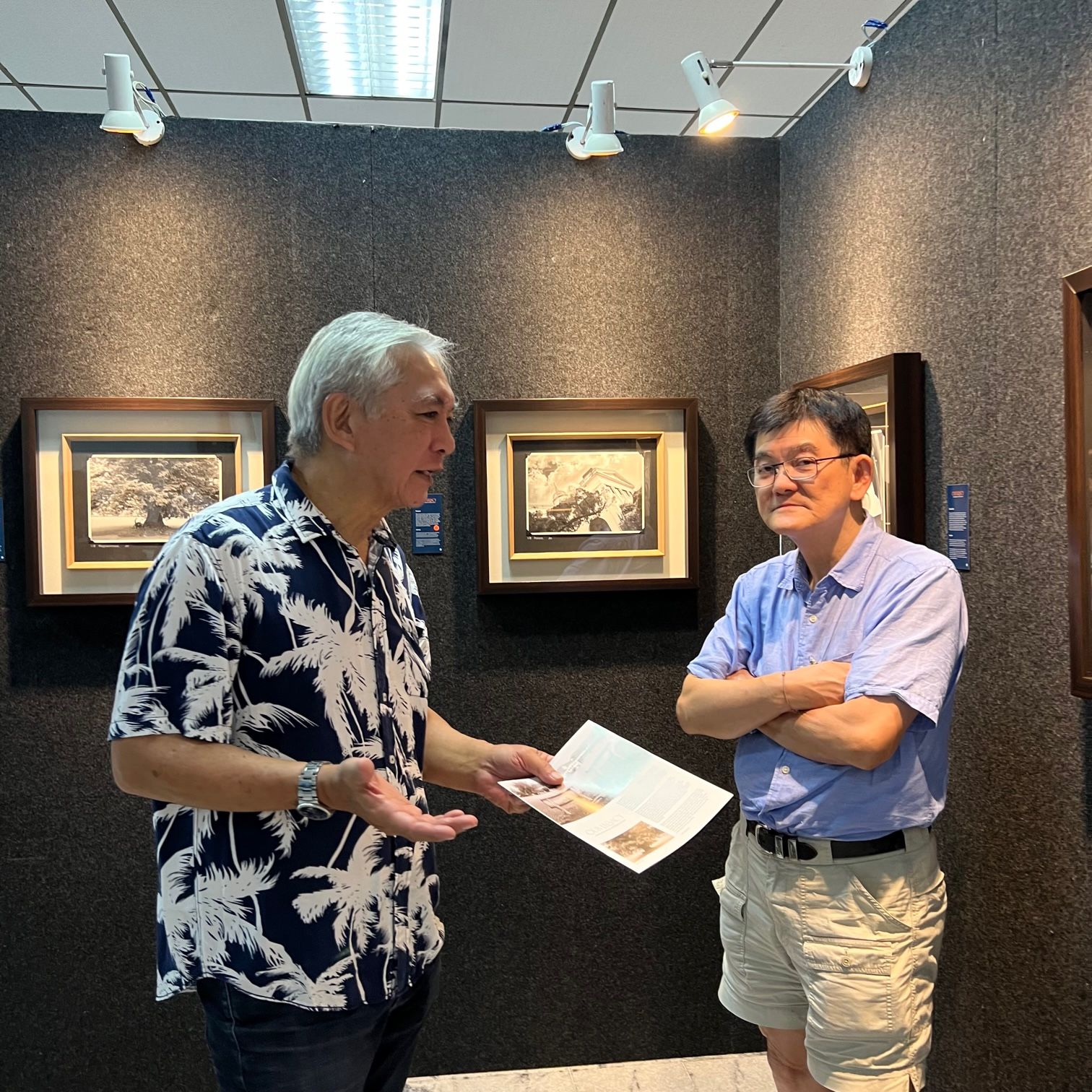

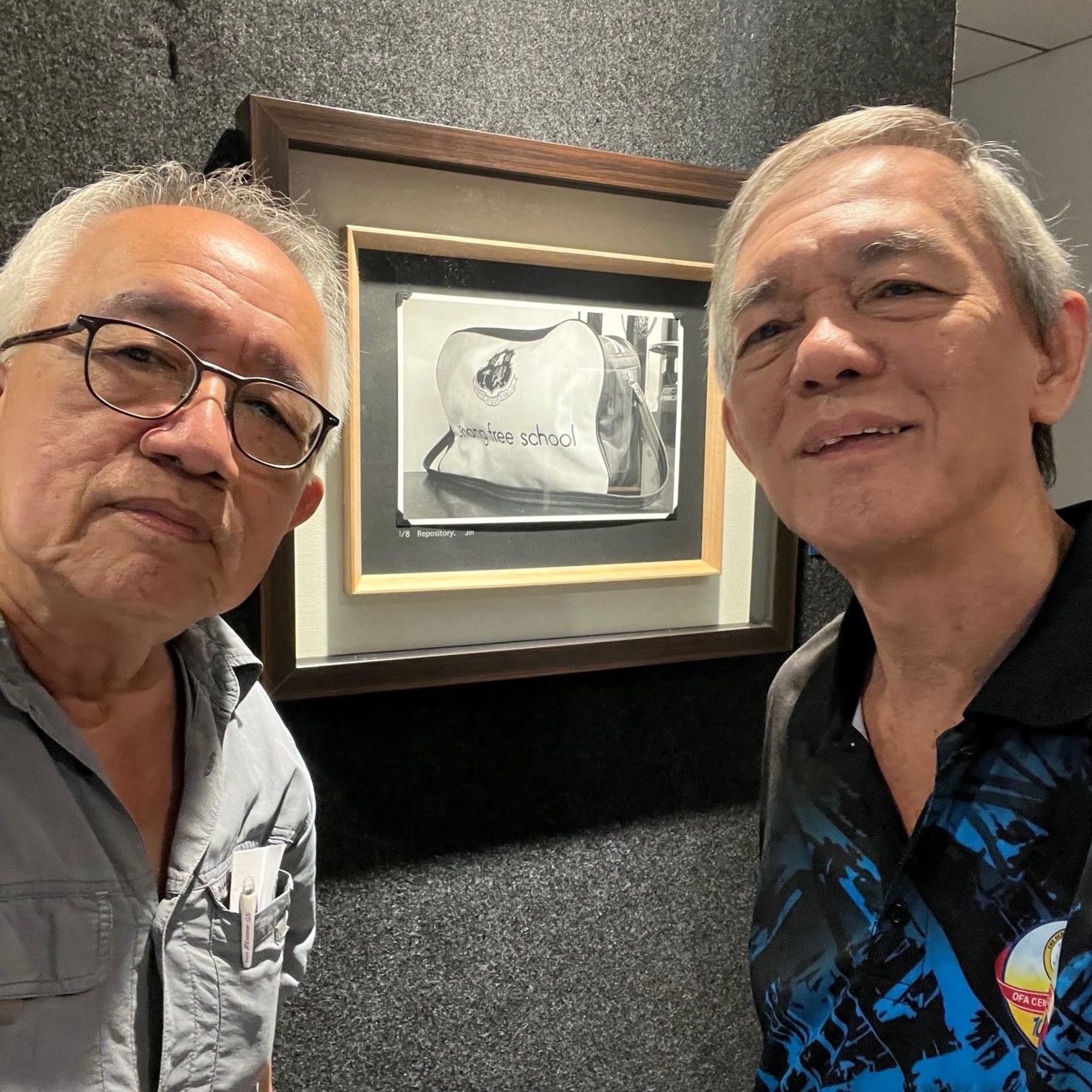

Attendees at the Reception at 3pm on Sunday, Sept 30, 2023, at The Old Frees' Association

Photography as art. Although I am not new to photography, I have not thought much about photography as art. At my first solo at A Place Where in Oct 2022, we organised two sessions with well-known photographers, namely, black-and-white specialists Eric Peris, KF Choy and Alan Ng, and photo journalists David Loh and Jahabar Sadiq. Their sessions were ably moderated by Khoo Hsu Chuang and Mahen Bala. (read here). It was there, and at an exhibition by Adam Seow at the Leica Store in Kuala Lumpur, that I began to grasp the idea. It was also then that I decided to use Penang Free School as the subject matter for my first photo exhibition. As for putting the ideas together in a coherent manner, I do not think, for the moment at least, I can do better than ChatGPT. Click below to read more.

Photography as art via ChatGPT

Describing a photograph as an art form, as opposed to a mere record of an event or place, often depends on the intention and execution of the photographer. Here are some circumstances and characteristics that distinguish photography as art:

- Creative Intent: When a photographer approaches an image with the intention of expressing emotions, ideas, or a unique perspective, it transforms the photograph into an art form. Artistic photography often involves a deliberate creative process rather than a simple documentation of reality.

- Composition and Design: Artistic photographs often demonstrate a thoughtful approach to composition, framing, and design. Consideration of elements like balance, symmetry, leading lines, and framing can elevate a photograph beyond a mere snapshot.

- Emotional Impact: Artistic photographs evoke emotions and resonate with the viewer. Whether through the use of lighting, subject matter, or composition, the photograph communicates a message or elicits a response that goes beyond the factual representation of a scene.

- Symbolism and Metaphor: Artistic photographs may incorporate symbolism or metaphorical elements. The photographer uses visual elements to convey deeper meanings, allowing the viewer to interpret the image on multiple levels.

- Technical Mastery: While not all art requires advanced technical skills, a mastery of the technical aspects of photography can contribute to the creation of visually compelling and aesthetically pleasing images. Understanding and deliberately manipulating elements like focus, depth of field, and exposure can enhance the artistic quality of a photograph.

- Personal Style: Photographers who develop a distinctive and recognizable style contribute to the artistry of their work. Whether it's a particular approach to color, a unique way of framing subjects, or a consistent theme, a personal style sets artistic photographs apart.

- Intentional Post-Processing: Artistic photographers often engage in post-processing to enhance or alter their images intentionally. This might involve adjustments to color, contrast, or the application of creative filters to achieve a specific aesthetic.

- Narrative or Storytelling: Artistic photographs often tell a story or convey a narrative. The composition, subject choice, and timing contribute to a visual storytelling aspect that goes beyond a simple representation of a moment.

In summary, a photograph is often considered an art form when it transcends the role of a mere record, engaging the viewer on an emotional or intellectual level through intentional creative choices by the photographer. The line between documentation and artistry can be fluid, and different viewers may interpret the same photograph differently based on their perspectives and experiences.

Attendees at the Reception at 3pm on Sunday, Sept 30, 2023, at The Old Frees' Association

Khoo Boo Teik gave a speech at my tea reception for the exhibition. I greatly appreciate that. We have been very good friends since the time we had long conversations about the school when we were Prefects in 1971-72. One thing he said touched me deeply: “Perhaps, most of all [in Free School], he established a close group of friends who to this day sometimes reminisce about the times they spent together in the Penang Hill, or by the beaches, or wherever else their fancy took them. In short, there was this small but intimate cluster of friends who left PFS for the world. But many of them are back, some in Penang. Which of us, having gone through PFS, would not understand that as one of our educational experiences?”.

The camaraderie we have is special, and it takes a person who understands me deeply to know how important this group (the “Boh Charp” Boys) is to me. They also sparked my wider interest in photography because I was one of two who had a camera handy for our various memorable times together.

Visitors at the exhibition

Slums of Bangkok, Manila, Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur. My second stint as a serious photographer occurred in 1982-83 when I, together with Dexter Tiranti of The New Internationalist monthly of Britain, conducted communications workshops for NGOs in Bangkok, Manila, Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur. In each of these cities, we took participants into the slums (like Khlong Toey in Bangkok) and got NGOs working there to give us guided tours. The workshops were conducted under auspices of the International Organisation of Consumer Unions. I was the Publications Officer at its Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific in Air Itam, Penang. We took lots of black-and-white photos and got them printed overnight. They were used by the participants to help them write stories about their experiences in the slums. Sadly, I only have one photo from those days.

Visitors at the exhibition and people behind the set-up

Rasa Rasa Penang. Boo Teik was witness to my third stint in photography. He wrote: “In later years Siang Jin came to Penang frequently, partly to work on state projects but also to visit his parents. We often got together for an evening meal during which we discussed his plans to popularise Penang’s culinary delights of the small and medium enterprise variety. So to speak, one could live one’s life in KL but prefer the food ‘at home’! The product of his research, which involved interviewing and connecting with stall keepers, was Rasa Rasa Penang. That book, no longer published, has become a lovely collector’s item, a little annotated coffee-table book with beautiful photographs of the hundred over stalls and their offerings, complete with simple, clear maps and contact details to guide the uninitiated to the premises.

“For his Rasa Rasa Penang project, he was again a journalist, but he worked at his leisure, undirected except by his own motivation, to produce a great culinary guide to Penang’s ‘street food’ that has become such a tourist attraction. I’d always imagine that Siang Jin’s education in sociology – at Kent and Leeds universities – made him document this vibrant, recession-proof trade in food and pay homage to a neglected cultural dimension of the making of a multiethnic urban community.

“Most readers focused on its information on food. One just has to see how full the Internet is of the ‘rasa-rasa’ books and guides that came after its Penang original. Siang Jin’s photographic essay, as it were, gave evidence of a process of cultural integration happening at its best – because its numerous culinary experiments occurred ‘below’ and still remain open to changes and exchanges.”

Personally, my most memorable takeaway from the project was the connection I made with the stall owners, some of whom, to this day, I am in touch with.

Wayfinder for The Street of Harmony. My final major outing as a photographer occurred around 2010-11, when Quah Seng Sun and I produced a “wayfinder” system for Georgetown’s “Street of Harmony” but that’s another story.

Boo Teik’s thoughts on ‘Our Legacy’. In this concluding section, I would like to quote Boo Teik’s comments on my exhibition and some of my photos. “[Siang Jin] had taken lots and lots of photographs over many, many years, using different kinds of equipment. Today’s collection is unusual. It comes as a tribute to The Old Frees Association’s celebration of its centennial year. With the Free School, we use terms like centennial, sesquicentennial, and bicentennial seriously: déjà vu, we’ve been through all of those!

“But Siang Jin’s interesting collection of 31 photos today captures a unique memory of PFS – or, should I say, a PFS fragmented into different elements. They are all part of the school – as it is remembered by one its fine sons after half a century. Yet they are not closely related: the first photo is not linked to the last photo in some neat linear composition. The annotations of the photographs show a deeply felt intimacy with the school, with its different components of sports, facilities, hall, library, etc. No classrooms are caught here, intriguingly!”

Boo Teik concludes: “No matter how we think of the Free School – and many, many are liable to think very fondly of it – PFS, like any other school, must be judged as the environment, in loco parentis, for its thousands upon thousands of students. Is it a good school or a great school? Or is it even a school in decline – now it doesn’t even have a Sixth Form science programme – which our memories play over?

“It’s not part of Siang Jin’s ‘landmark memories’ to supply an answer. The exhibition is a recollection, and a very fine recollection, of the artist’s favourite haunts, relived half a century after he left school. I very much hope that someone else would mount an exhibition of old and new photographs that capture, among others, the humanity that continues to go through the Penang Free School. After all, what is a school if it is not a collection of its students and teachers, good and bad, who shape its development over two centuries? Or perhaps, Siang Jin, in his tireless pursuit of artistic and social themes will hold a second exhibition along those lines.”