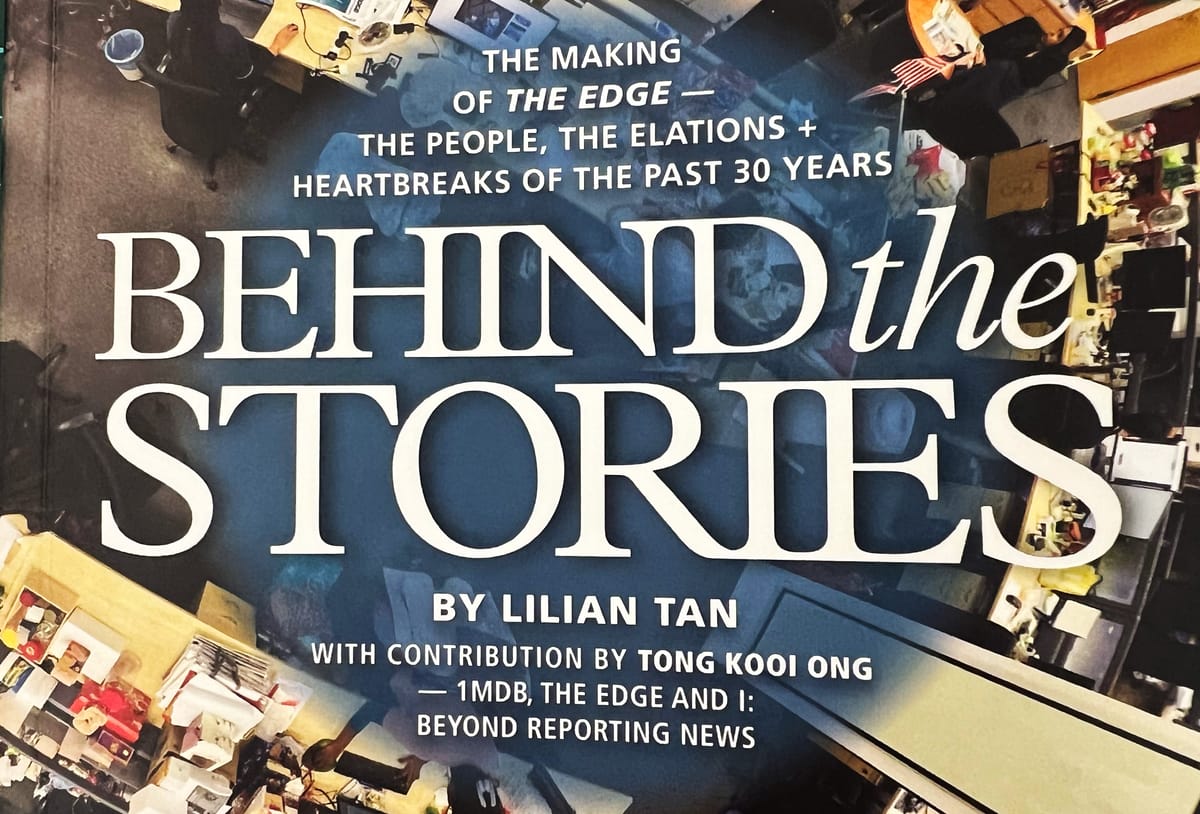

Four cheers for the backroom of our village

As Behind the Stories was being put together, Kay Tat asked pioneer staff – Tan Boon Kean, Au Foong Yee, Azam Aris, Dorothy Teoh, Chong Cheng Hai and me – to write something about our days at The Edge or theSun that meant something to us. I chose to write about the “backroom”, the unsung heroes and heroines of our profession. They comprise copy editors, layout and design staff, photographers and production personnel. The following were four occasions “when this group really shone by itself and in their collaboration with other facets of the business”.

I WAS, FIRST AND FOREMOST, a production person in print media. We revelled in abbreviations like DPI, CMYK, CTP and H&J. We talked frequently about grids, copyfit, leading, dot gain and grammage. Our days were dictated by multiple deadlines and offstone times. We were the backroom people, more often than not the unsung heroes and heroines of the business.

I would like to relate a few episodes during my years at The Edge and theSun when this group really shone by itself and in their collaboration with other facets of the business.

Two papers, one backroom

In 2001, when we launched The Edge Singapore, we sent over our A-team comprising BK Tan, Ho Kay Tat, Edward Stanislaus and Suresh Kumar. Their office at Cecil Street would gather and edit material, create brand awareness, market advertising space and build a circulation base. Production would remain in Malaysia, a lower-cost centre, with ample experience and resources.

A lot took place before the launch. Our production chief Thomas Chin had to ensure we could send high-resolution PDFs to Singapore’s KHL Printing and that the PDFs were suitable for their CTP (computer-to-plate) printing system. The transmission bandwidth had to be adequate; the colours had to be co-ordinated with KHL’s printing presses.

On the editorial-production floor in KL, production editor Ooi Inn Leong split his team into three: one to handle The Edge Malaysia, another for The Edge Singapore and the third, our other standalone publications like Haven, Personal Money and Off The Edge. Elaine Lim took over production for Singapore while Pushpam Sinnakaundan handled Malaysia. Each had a group of copy editors and graphic artists. However, with the hurly burly, many had to multi-task. Sharon, our art director, had her hands full too, having to take on almost double the normal load.

Handling Singapore presented new challenges. For example, the pages that were laid-out in Kuala Lumpur had to be sent to Cecil Street for proof-reading. There was much to-ing and fro-ing on corrections before the PDFs were finalised in KL and re-sent to Singapore for printing.

One indication of the volume and intensity of work, with added machines and people, was that the air-conditioners, once freezing cold, could no longer cool the space. We had to add more units. After a few months though, things were humming again in the backroom. Humming at a level of much greater volume and intensity, I might add.

Fail-proofing theSun

In 2002, when theSun came under Nexnews Berhad’s umbrella, the fate of the two companies, The Edge Communications and Sun Media Corporation, became inextricably tied — for a time at least. The Edge team, which took charge of strategic management and chipped in at all levels, decided that theSun should be relaunched as a free paper. When news of this broke, there were a lot of misgivings.

But we were steadfast. We had studied carefully free papers such as Singapore’s Streats and London’s Metro. Knowing that 80% of the income of all successful publications came from advertising, we embarked on a strategy that (1) cut overall costs by decreasing pagination (from 80 to as low as 24) and staff numbers (from 500 to 150); (2) increased circulation to 150,000 then finally to 300,000, to match or surpass other national English dailies; this was to satisfy our advertisers who wanted reach and (3) targeted circulation at PMEBs (professionals, managers, executives and business people), by placing our copies for pick-up at lift lobbies of numerous office towers and a wide range of suitable consumer outlets including 7-Eleven, Starbucks and McDonald‘s.

Production-wise, we had to design this no-frills “AirAsia” of the print media to suit the overall model. We wanted it to be a 20-minute read with story count that matches other dailies. Each page would ideally have a lead story, a second lead, a photo with a strong caption, and lots of one-paragraph stories with catchy headings. Research has found that headlines, captions and “fillers” are the most-read items on a page. Using this design, we could have as many as 12 stories per page.

Geographically, our targets were the Klang Valley and urban centres along the west coast of the Peninsula. We had two print runs: the first was to start at 10pm and end at midnight so that the lorries could collect them and drop copies on two routes to the north and south, ending in Penang and Johor Baru respectively at daybreak. The second print run, for the Klang Valley, ended around 5am. However, batches would roll out as early as 3am.

Days before the launch, with so much going on, the page designs were known only to Tony Chong, the designer, and me — in our heads because there was no time to do a mockup and share with others. To my utter shock, Tony fell ill and was hospitalised as we were about to roll out. Knowing that managing editor Chong Cheng Hai and chief sub Kong See Hoh were old hands, I resorted to drawing the pages on “dummies” while they translated them into the DTP (desktop publishing) system of the paper. Although we started from scratch, these seasoned production people could empathise with what I did and picked up immediately. They were already re-adapting the pages for specific needs, even into the first week.

I could not sleep the night of the launch, fearing people would reject us and throw theSun away on the streets after reading. At dawn, we drove around Kuala Lumpur anxiously looking for strewn paper and there was none! It was a great relief. We found out later people took them to their offices to share, and back to their homes after work.

Plan B for SARS

When SARS (Severe Respiratory Syndrome) broke out in 2002, our first response was to safeguard our staff. The executive assistants on all the seven or eight floors were provided thermometers and asked to take charge of SOPs like ensuring the cleaners sanitised office equipment twice a day, telling all staff with coughs and fever to work from home, and preventing outsiders from entering the premises — that included staff from Singapore. There was no exception. It included BK Tan and Ho Kay Tat who had to stay away until they satisfied quarantine conditions.

Plan B, with an elaborate distance-working system, would benefit us in two ways: Keep our staff safe and take advantage of any situation where a competitor should suffer an outbreak and closed its offices. We trial-ran the process, section by section, until we were satisfied remote working was a possibility. Under such circumstances, we would leave skeletal staff to operate the final phases of production.

Working from home, the writers, photographers, copy editors and artists of each section had to co-ordinate among themselves over the internet and phone system to create final artworks for every page. Thomas was at the core of this decentralised system.

Since broadband was not widely available then, he would go round to the homes of all key designers to collect CDs or DVDs with high-res PDFs and then to assemble the publication at the office. It worked. There was no outbreak in our offices but it was reassuring to know that we could have pulled off Plan B had any untoward event occurred.

Later, we took the SARS SOPs developed at The Edge and work-from-home system to theSun too. They also worked, but with a lot of modifications to suit the work environment. Fortunately, the SARS outbreak did not last long.

Devolution, teamwork and communication

When the work of managing two weeklies at The Edge and an untested business model of theSun took hold, I decided that, to perform more effectively, we needed to devolve decision-making and increase communication among the various sections. We expanded attendance at the monthly management meetings to include all the department heads (from five people to nearly 20). Lorraine Chan, my PA, wrote out pages of minutes each time, focusing on to-dos so that we could follow-up on the next meeting.

Open discussions enabled each section to know and understand what the others were doing more clearly. Each section was given its own set of profit and loss statements to empower them with accountability. These decentralised organisational dynamics worked well and our numbers continued to grow over those years — circulation, revenue and profitability.

In my years at The Edge and theSun, I still stuck to my forte as a production person, but one who had fashioned a platform on which I was not the conductor (like that of an orchestra) but a facilitator who allowed a flurry of creative activities among specialists – more akin to jazz.

I was a founding director of The Edge in 1994. My last position was managing director of The Edge and theSun. I left in 2005.

*Republished with permission