Tale of two book covers

BOO TEIK’S penchant for dissecting the structures of thought and examining the consequential actions of Malaysian leaders and the people around them have resulted in three main publications: one on Mahathir Mohamad, another on an array of issues during the Mahathir era and their implication for the future, and the most recent on Anwar Ibrahim. I am fortunate to have played a part in the design of the covers of two.

In mid-2003, Zed Books Ltd, the publisher of Beyond Mahathir: Malaysian Politics and Its Discontents (read here) was finalising production when it found it needed a cover image. Boo Teik, my friend from schooldays who was familiar with my art, asked if I had an appropriate piece. I invited him to my home to rummage through my collection. Finally, we agreed on a pleasant-looking piece called “A Day in the Park” (acrylic and ink on paper, 11.75in H x 16.5in W, 1988).

I was very proud of the contribution. After the book appeared in November 2003, I quickly bought a number of copies and presented them to senior staff of The Edge and theSun as Christmas presents.

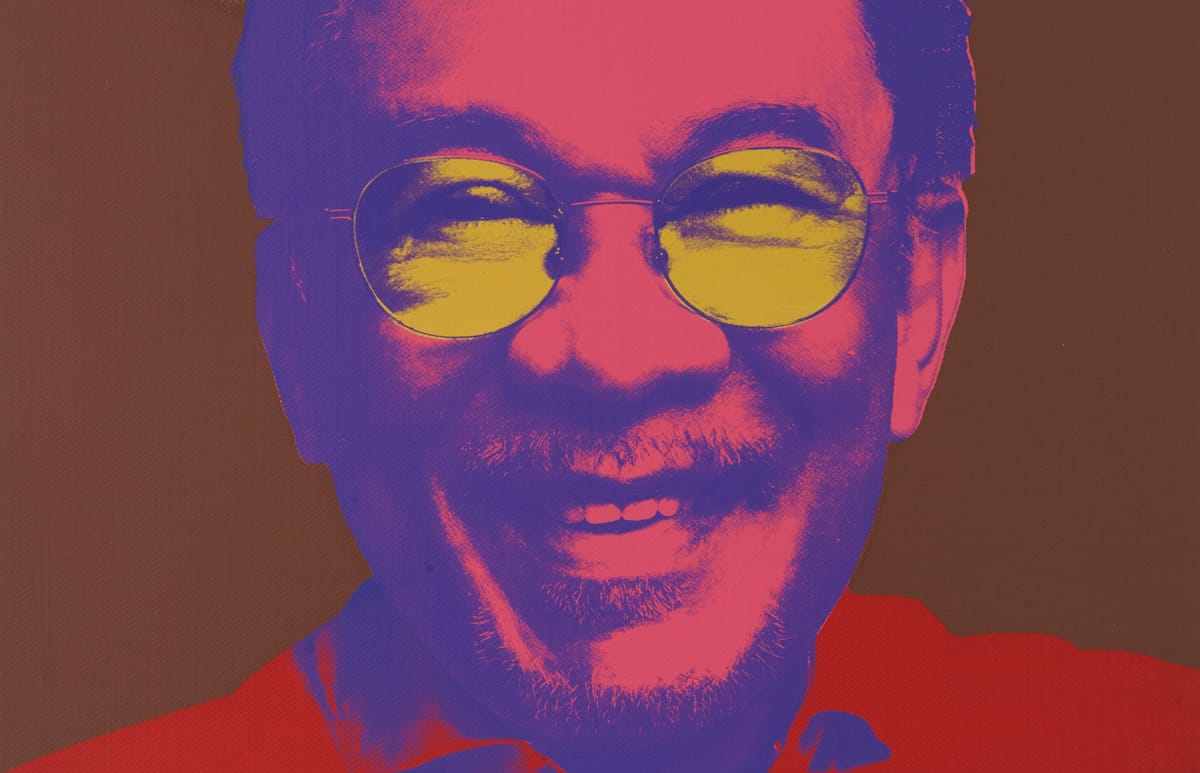

So when Boo Teik asked me in late 2023 to design the cover of his latest book, I gladly agreed. For Anwar Ibrahim: Tenacious in Dissent, Hopeful in Power, I would be doing more than providing an illustration. We went through several ideas and settled on one that depicts the works of artist Stephen Menon; he happened to have completed the prints for an upcoming exhibition slated for end-February. He has kindly allowed us to use them. The Warhol-like prints lend themselves to a Warhol-inspired design. Moreover, their wide range of colours can be taken to represent the different deportments of Anwar’s person and the various stages of his colourful history.

During the launch of the book at Crown Crystal Hotel, Petaling Jaya, on January 6, 2024, Boo Teik gave a speech in which he answered five questions. I find the contents rich and interesting, much like a sneak peek into the mind of an author. I am carrying them verbatim below.

How did you come to write on Anwar Ibrahim?

I’ve always wanted to write on large, major issues, not to say, epic events, in politics even for a small country like ours. I’ve published on Mahathirism, the political discontent beyond Mahathir’s first regime, and, now, Anwar Ibrahim and the transformation of politics in Malaysia. Each of these books tackled a subject that I’d never thought would be the last word on the subject. I only wanted to set a standard on the subjects on which other writers were welcome to improve.

There was little virtue, it seemed to me, to write on small issues even if one could finesse one’s interpretation of them. Yet I did my share of those: the pressures of academic life required interpretations of limited issues for publications in many kinds of sources. One frequently wrote relatively short articles to address the sudden eruptions in political economy, or an unsuspected crisis of a judiciary that couldn’t protect itself, the systemic flaws of the electoral system, the disgraceful conduct of political parties, the biographical sketches of politicians, admirable or otherwise, and so on.

I’d written many commentaries for the Aliran Monthly, Malaysiakini, and other mass media that gave my opinions on contemporary events – such as the East Asian financial crisis of 1997, the fall of Anwar Ibrahim, the histrionics of UMNO figures, the demonization of the Chinese community, all the way to the exciting emergence and calamitous collapse of the first Pakatan Harapan administration.

From the dark days of the beginnings of Reformasi to the darker days of the backdoor governments, and the darkest days of the Covid-19 pandemic, I saw Anwar’s tenacity at work. It was remarkable that anyone could fight as he did and succeed after 25 years of being under major constraints. Thus, I wrote on the parlous condition of Malay politics (which remains the crux of the present situation), the making of the humane economy (which expressed Anwar’s hope), and the two unrealised Mahathir-Anwar transitions of the premiership (which had brought much anger and despair to large sections of the public). And, then, when he became Prime Minister in November 2022, it seemed to be appropriate for a retired academic to complete a book on Anwar’s politics – roughly of the past 25 years.

What is the core of the book?

My book covers a lot of material: Anwar’s charisma and supposedly chameleonic character; his fight against hegemony and corruption; his Islam and ideas on economic reform; his involvement with the great dissident movements of our time; and so on. Sometimes, I must admit, the connections of these components of Anwar’s politics confused me somewhat.

One way to deal broadly with this is to cite a long quote from Lytton Strachey, a pioneer of the art of biography. Writing of Florence Nightingale in Eminent Victorians (London: Chatto and Windus, 1918), Strachey said that:

‘Everyone knows the popular conception of Florence Nightingale. The saintly, self-sacrificing woman, the delicate maiden of high degree who threw aside the pleasures of a life of ease to succor the afflicted, the Lady with the Lamp, gliding through the horrors of the hospital at Scutari, and consecrating with the radiance of her goodness the dying soldier’s couch – the vision is familiar to all. But the truth was different. The Miss Nightingale of fact was not as facile fancy painted her. She worked in another fashion, and towards another end; she moved under the stress of an impetus which finds no place in the popular imagination. A Demon possessed her. Now demons, whatever else they may be, are full of interest. And so it happens that in the real Miss Nightingale there was more that was interesting than in the legendary one; there was also less that was agreeable.’

How different has Anwar been compared to Florence Nightingale from this perspective? Let us quickly see.

Everyone knows the popular conception of ‘DSAI’. Over half a century he was by turns the Malay nationalist student rebel, the Islamic radical motor of dakwah activism, the alleged organizer of the Baling demonstration, the ISA detainee, the leader of the anti-Societies Act campaign, the co-opted rising star of UMNO, the anointed heir apparent to Mahathir, the persecuted anti-corruption reformist, the reinvented Reformasi dissident, the returned Opposition leader, the inspiration of a reunified Opposition, the symbolic force of the 2008 tsunami, the three-time ‘failed PM wannabe’, and the three-time imprisoned threat to three prime ministers. At critical moments, he threw aside the option of a life of comfortable irrelevance to rouse the sleeping masses. He was a prisoner of conscience with a blackened eye, who was jailed for eleven years of his prime political life, often in solitary confinement. He bided his time to return to politics and lead a campaign of reform.

Isn’t this summary, though complicated, familiar to all of us? But was the truth different? Was the Anwar of fact neither as his opponents daubed him, nor as his allies portrayed him? At critical junctures, had he not worked in another fashion, and to another end? Had he not moved under an impetus which found no place in the political imagination?

Might it not be said that a Demon possessed him? We can think of the Demon as his assumed obsession with becoming Prime Minister, or his preoccupation with charging politicians in high places with corruption, or his supposed interest in Islamizing Malaysian society. And demons, let’s agree with Strachey, are full of interest. And, therefore, there was more that was interesting in the real Anwar than in the legendary one. It only wanted a book to explore what was interesting about him, even if it meant leaving out parts of Anwar’s political life.

In what ways is this book different from others written on Anwar?

Mine is an academic book. It is a popular book, too. I’ve tried to write so as to be accessible to many readers, particularly Malaysians. Sometimes one is borne by the flow of language to denser and denser expressions that get more and more incomprehensible! Yet, and please allow me to say it, good writing presupposes good reading. And reading means engaging with an author. I don’t ask much of readers beyond their capability in English up to a Form 5 or 6 level. I hope, though, they will engage with my views and arguments.

I haven’t paid much attention to theoretical issues which upset some of my colleagues in the past, especially when I submitted pieces to academic journals. But, instead of merely presenting facts, I’ve argued every important issue in the book. Maybe that’s somewhat different from other books.

There’s a point to mention here. My book on Anwar pays attention to the tremendous rise of popular disobedience over the past 25 years. I hadn’t thought I’d see that in my lifetime. From September 1998 to this day, every regime has been met by massive dissent. This unexpected development supplies the sociopolitical context for everything else in the book. Sometimes the dissident Anwar could move that dissent. Sometimes the opposition would force him onwards. Let us sum up the phenomenon in this way: One cannot understand the politics of the past 25 years without a feel for Anwar. But one cannot explain Anwar without grasping the politics of the past 25 years.

Let me quote the historian, E H Carr, who wrote that, ‘What seems to me essential is to recognize in the great man an outstanding individual who is at once a product and an agent of the historical process, at once the representative and the creator of social forces which change the shape of the world and the thoughts of men’ (What is History? Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: 2001).

What do you think of the future, and especially Anwar’s future?

One answer is easy to give if one wants to speculate, spin, gossip, and spread rumours! Another answer is difficult to offer if one wants to cast rational arguments around specific details. So many political areas are in conflict. They must be resolved in slow but steady ways: look at the anti-corruption cases, or the race- and religion-based attacks on the administration. In other areas, quick but complex responses are needed, and yet the public may not have clear ideas about the implications of policies: look at Gaza where historical, rational and caring responses meet against the opposition of powerful states.

But perhaps only one situation is called for here: Anwar is likely to remain as Prime Minister to the end of his present government. Beyond that, all parties and coalitions must consolidate their strength, neutralize their opponents, boost popular confidence, coalesce their partnership … what else?

Are you writing another book?

Believe me, I’m thinking … The good thing about being retired is, as Benedict Anderson once said, that one can read or write on anything one wants. One no longer has to read or write to influence one’s students and peers. Maybe I should write on a different political topic or a subject quite unlike what I’ve done before. Saying this presumes that I’d be prepared and would have the resources to put in long hours of research into either topic for no obvious gain!