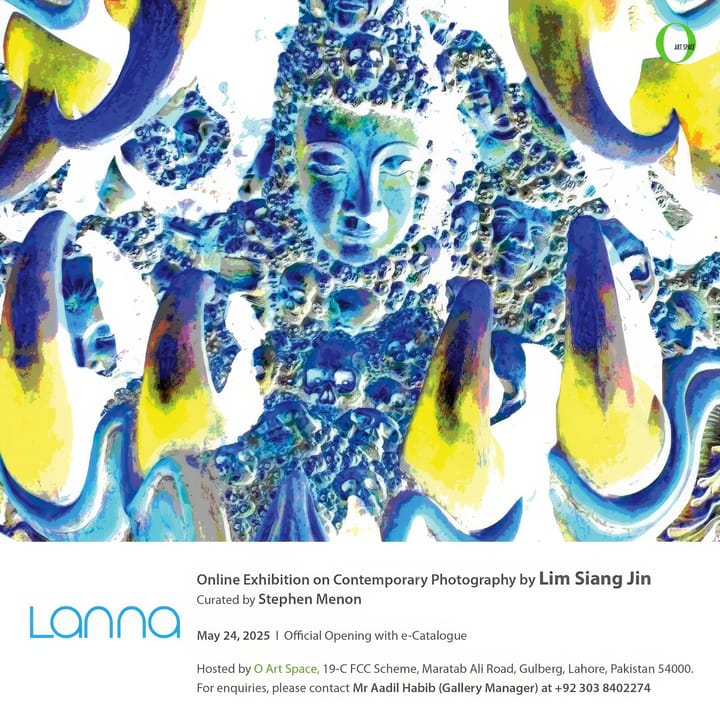

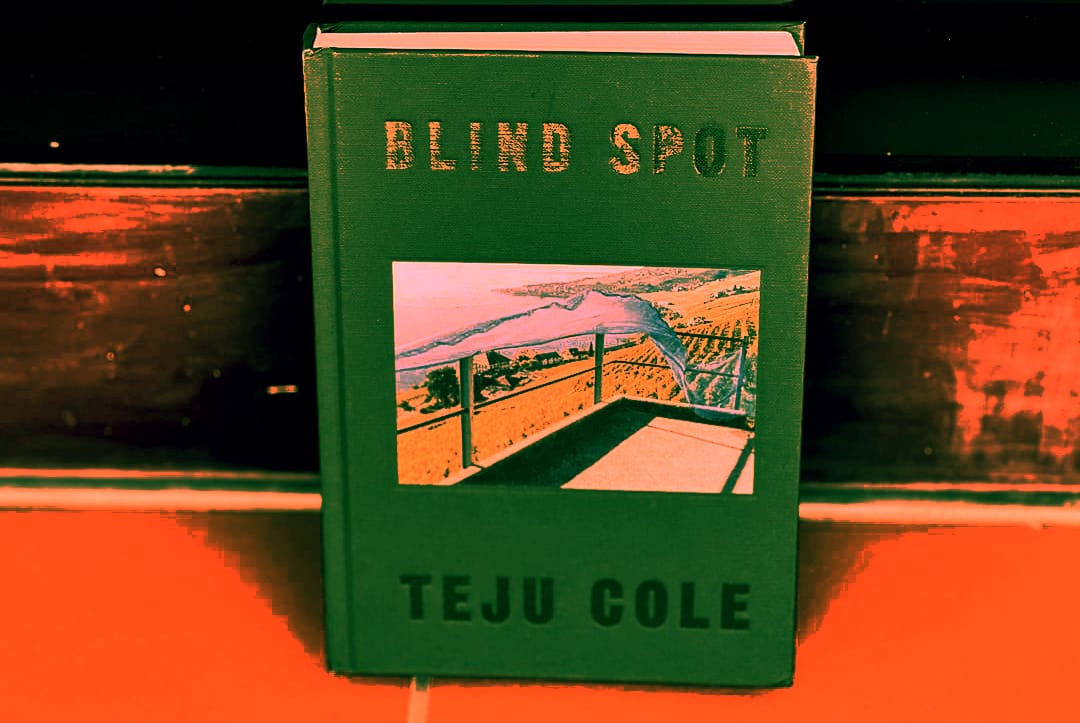

Notes on Teju Cole's Blind Spot

I STARTED to read Teju Cole with great reluctance, knowing he may rekindle a feared tendency in me: Getting bogged down in the convoluted thinking of others. Surprisingly however, the premises of his works are straight forward and appealed to me from the get-go, from the time I read Siri Hustvedt’s foreword to his Blind Spot and the first few pages of the 332-page book.

My friend Tow Keang who recommended the book knows me well. He also suggested I write this piece.

Cole’s Blind Spot combines photos and prose — very dense prose like poetry, and critics have likened his writings to phenomenology. It’s a large field of thought. I will just make a quick reference to Maurice Merleau-Ponty as a starting point since Cole mentioned him in his works. In his Phenomenology of Perception, Merleau-Ponty summed his views as follows:

Insofar as, when I reflect on the essence of subjectivity, I find it bound up with that of the body and that of the world, this is because my existence as subjectivity [= consciousness] is merely one with my existence as a body and with the existence of the world, and because the subject that I am, when taken concretely, is inseparable from this body and this world. [408]

In other words, consciousness and the “real” world are inextricably intertwined – as far as each individual is concerned. “Consciousness is embodied (in the world), and equally body is infused with consciousness (with cognition of the world)”, in the words of another commentator.

Cole’s photo-prose combinations, like “Tivoli” above, have been described as “choreographed dance of words and pictures” (read here) or “ ‘a tangled tree of meanings’ between text and image, a metaphorical wood.” Siri Hustved wrote the following about “Tivoli”:

“Spring, even in America, is Japanese”. Really? That’s a surprising sentence. But when I look at the photograph, the tree’s shadow evokes the countless images of branches in Japanese art, usually in spring flower. (Here the blossoms are implied by the association but are absent from the image). Spring, the time of birth, of bloom, of stirring motion.

Cole transported us to the obverse from the second sentence: “It is not only the leaves that grow. Shadows grow also. Everything grows, both what receives the light, and what is cast by it. There is more in the world, all of it proliferating like neural patterns. Almost all of it: it is also the most melancholy season, for, as Alkman says, there is nothing to eat.”

We are taken to a truism about the season of growth (via Alkman, the poet from ancient Sparta). Emerging from winter which has drained resources, spring is a time of hope however food is scarce. Alkman wrote: “made three seasons, summer / and winter and autumn third / and fourth spring when / there is blooming but to eat enough / is not”.

We are also drawn to the metaphor of neurons, sparking the idea that thought and introspection are spreading out too. Negative ones, “for at times in spring, even the emotional granaries are depleted”.

In another example, “Vancouver”, Cole wrote:

In some of my dreams I fly. In some of my dreams I fall. Both sometimes appear together in the same dream, and my body leads me there by some respiratory change, faster breathing or slower. In life, we seldom fall, but fly often. In dreams, we fall often, and fly seldom. Life and dream I balance on this breath. In Don Quixote, there's the young girl who often I dreamed of falling down from a tower and never coming to the ground. She would wake from the dream to find herself as weak and shaken as if she had really fallen. On a recent flight, I fell asleep, and dreamed of falling. Then I heard the captain’s voice, and woke up inside a world of cloud and a soft descent, and was as shaken as if I had really fallen.

For my own search, I am excited, for example, by the fact a film was made using Quixote’s falling girl. View the trailer here. It opens another avenue for me to explore.

Run-of-the-mill photos? Cole’s photos are not spectacular; they are more in line with those of Stephen Shore who has said: “To see something spectacular and recognise it as a photographic possibility is not making a very big leap. But to see something ordinary, something you’d see every day, and recognise it as a photographic possibility – that’s what I’m interested in.” Read here and here.

Enhancing my journey into nostalgia: One genre of works that can benefit from Cole’s works is my “nostalgia” projects, like Our Legacy: Landmark Memories of Penang Free School. View here. “Perplexing” below, a part of the project, for example, could be re-captioned to bring deeper and wider meanings, although, to be sure, Our Legacy was never meant to brim with complex meanings.

Building on Cole’s dense prose-plus-photos as didactic tools: Like poetry, dense prose with photos, can be used to let learners expand the ways they acquire and share knowledge. I would like to examine two in the works of mine: (a) Drawing complex ideas from images, condensing them into a few inter-related words, and making sure the image-text relationship remains as viable as possible, and (b) Looking at the relationship between the subject and the object, between text and image.