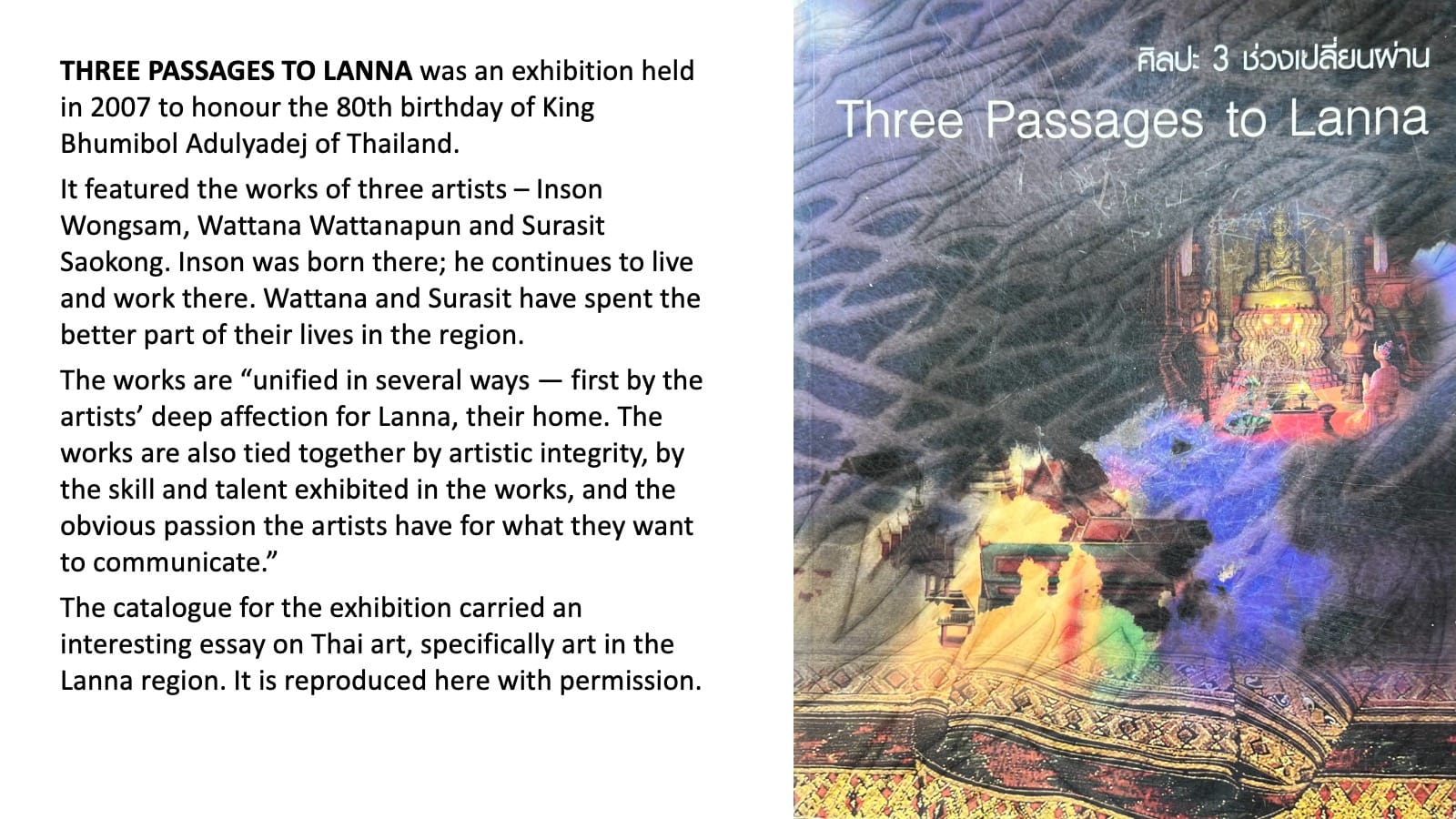

Three Passages to Lanna

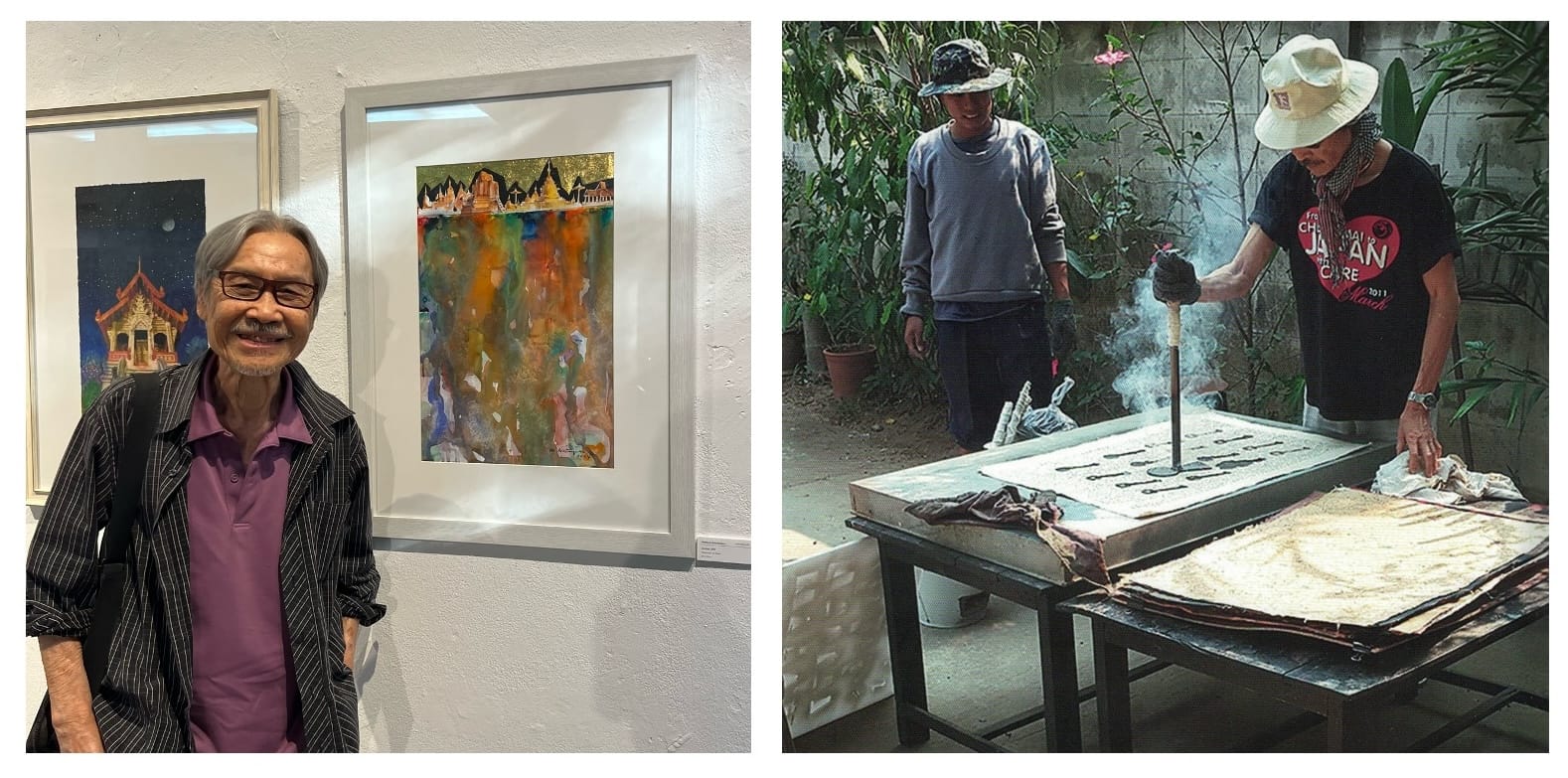

MY RECENT nine-day trip to Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai in early January has been most fruitful. In Chiang Mai, I was hosted by renowned artist Wattana Wattanapun. I made a presentation on “Art & Storytelling” at his gallery and we went to the galleries of (1) Inson Wongsam and (2) Surasit Saokong and his wife Sriwanna. While visiting them I came across this very interesting piece and sought permission to reproduce it.

Lanna and historic cultural changes

We often hear people say “Thailand is not Bangkok.” By that they mean that there is significant cultural diversity within Thailand’s borders. Lanna, the northern region of the country, has long had an evolving cultural tradition distinct from that of Central Thai culture. Both government policies and private sector expansion have recently affected Lanna culture, with dramatic impact. Lanna has been absorbing outside influences for 700 years, and the present-day situation is no different, except that it is much faster, farther-reaching, and in some ways, destructive.

The two hundred years of Burmese influence over Lanna is usually spoken of in negative terms and no doubt it was felt as negative by the Lanna ruling class. Ordinary people in both kingdoms, however, had always crossed the border freely to exchange goods, and the exposure to one another’s culture affected all aspects of people’s lives on both sides of the border. The Burmese influence on Lanna temples, for example, added charm and refinement, and such an influence cannot be considered negative. Most likely the common people who went to their temples to make merit would not have been bothered by some of the new Burmese architectural and decorative art; they could still express their religious faith no matter what their temples looked like. So when we talk about cultural change, positive and negative, we need to consider the consequences on the individuals in the affected cultures.

Some causes of cultural alienation

When a dominant culture attempts to impose unity upon a culturally-diverse geographical area in order to promote unity within its borders, some unintended consequences can occur. Because a government or cultural ideology doesn’t necessarily reflect the reality of individuals’ day-to-day lives. People in the minority cultures can be made to feel alienated by their rulers, as if they were strangers in their own land. They may feel confused and lack confidence, which reduces their capacity to contribute to society. The imposition of a strong central culture on minority culture pervades all aspects of their lives — education, political expression, economic opportunities and limitations, religion, and the arts, for example.

Let’s look at the effects of cultural domination in the current art scene in our country. National awards for both traditional and contemporary art tend to use criteria that overlook the rich diversity here. It is as if there is only one recognised expression of traditional art, the one that reflects the Central Thai artistic tradition. National promotions tend to overlook the lively and energetic regional art that does not fall within rigid standards. As a result, the art of ethnic minorities rarely enjoy recognition on a national level.

Preserving historic Lanna treasures

Over the centuries, a rich tradition of Buddhist art thrived in Lanna religious architecture. The building of temples was like the sculpting of priceless gems with the loveliest jewels saved for the crowns of mountain temples such as Wat Phrathat Doisut and Wat Phrathat Doi Suthrep. These graceful creations became even more beautiful as trees and flowering plants matured around them. These treasures have enriched the lives of many generations and should be valued and respected for the cultural jewels that they are.

Unfortunately, recognition of regional artistic treasures is not usually the first priority of politicians. Temple maintenance or restoration isn’t included in budgets, because the results of proper maintenance and restoration can’t be measured in the usual economic terms. The few temples notable enough to attract officials’ attention may be even more unlucky, for there is usually little research done regarding the origin, building techniques, building materials, and traditional aesthetics of the structure. Renovation proceeds without the proper knowledge or consultation with the right people. Budgets and time frames are deemed more important than the preservation of a historic and aesthetic treasure, and as a result, many masterpieces of Lanna art have been permanently damaged.

A related controversy involves the building of hotels using temple architecture or authentic religious antiques. Many people are confused about the art in these expensive buildings, done by professional architects who profess to understand art and culture. The Constitution requires public hearings, but somehow the stakeholders have little chance to voice their opinions, either because they don’t know what to say or because mega-projects follow the letter of the law but not its spirit, and the right people are not given a chance to speak up. In addition, many people are not clear about what should and shouldn’t be done, because so little attention and education has been given to the respectful preservation of our artistic heritage.

Lanna and globalisation

Politicians and some business people have recognised the value of selling so-called Lanna culture for handsome profits. Two new, contrived extravaganzas are the World Royal Flora and Night Safari projects. In both, human exploitation of nature for profit seems to be the principal purpose. Neither event really has anything to do with what has traditionally been part of Lanna culture. Any trappings of actual Lanna culture are used only to produce profits for the investors, not to nurture or enhance the culture or the local economy. Calling the World Royal Flora “Rajaphruek 2549” supposedly represents the respect the project creators wish to pay to the King. Yet they don’t seem to know quite what to celebrate. Thais have always prided themselves on being self-sufficient, yet there is not a trace of self-sufficiency in these two projects. In the end, these two projects bring about the death of many plants and animals, hardly something to be proud of.

Artistic heritage and the culture of imitation

There has been an unfortunate tendency to confuse respect for our artistic heritage with blind imitation of what has already been done time and time again. Art education in the schools relies almost exclusively on imitation. We need to turn more attention to building upon our artistic heritage through thoughtful and creative artistic expression. Most entrepreneurs do not understand or value such creativity, so they instruct their craftspeople to copy objects from photographs to fit certain dimensions and certain practical requirements. While their situation is understandable, it is unfortunate that real talent and creativity are undermined each time imitation is the only way our artistic richness is added to.

The evolution of contemporary art in Thailand

The government has recently established the Office of Contemporary Art. This agency has an organisational structure similar to that of other government departments and ministries and focuses on contemporary art within the framework of the national government policies. Government involvement in contemporary art can be positive or negative, and sometimes both, but art truly flourishes when it is not under the restrictions of an official body.

Contemporary art draws its vitality from its freedom from national borders, standards, and expectations. In some countries, there are national and city budgets for art, and the artists who receive their grants are free of most standards and expectations. There are inevitable clashes between what the artists produce and what some people in the public do and don't want to be done with their tax dollars in the name of art. Such dialogue is beneficial and raises public awareness of art and its possible places in society.

Contemporary Thai art follows international trends in that some current art does not incorporate any Thai or Lanna characteristics. Unfortunately, if artists do not include recognisable Thai features or designs in artwork, their art is excluded from consideration by our government agencies, no matter what value it may have for Thai society. In some cases, the government chooses clumsy and tasteless public art that superficially qualifies as Thai over thoughtful, creative art that may challenge passers-by to consider their assumptions in ways that will be beneficial for our society. We see many examples of substandard work in our large intersections and city plazas, simply because those works are superficially Thai, whether or not they have aesthetic value.

The search for the meaning of contemporary art in Thailand needs to recognise two kinds of changes going on these days:

- Internal change, or change specific to Thai culture. For example, when Professor Silpa Bhirasri established Silapakorn University, most artists who studied with him continued to produce art with the tools and media they learned with him — canvas, paint, and bronze, for example. They studied world art history extensively, in addition to perspective, colour theory, landscape, seascape, still life, composition, and the art of their own Thai culture especially the traditional art of Central Thailand. These artists’ works reflected the universal principles of art they had learned, combined with content taken from Buddhism and Eastern philosophy.

- External change, or influences from beyond our borders. Hundreds of artists have gone abroad to study or share ideas and techniques with their colleagues in other countries. The work of these Thai artists is often displayed in exhibitions overseas, side by side with work of other international artists. Sometimes such art reflects social and political issues, and the artists have become social and political movers. Some express their social concerns in their artwork — concerns related to violence, corruption, women’s rights, the environment, and the treatment of ethnic minorities, for example. They hope to challenge harmful assumptions and possibly bring about social change through the power of art.

In Thailand, the era of contemporary art began less than fifty years ago. At the beginning of that time, art was not a subject of conversation in our society. Mass media ignored it for the most part. Now there is at least one art columnist in almost every magazine and major newspaper. Though most art critiques are not of high quality, most media devote some space to recognising art. Galleries have multiplied and there are even auctions of artworks. Thai artists have begun to be represented in international collections, and some notable collectors of art are Thai.

The arts tend to grow along with improvements in education and economic growth. Some people here can now make their living as artists, and a number of them have become well respected and famous. What a contrast from 35 years ago when some important Thai artworks were slashed and destroyed only a few short years before their creator was recognised nationally and internationally for making important cultural and social statements with his art.

Traditional Thai art does not emerge from a vacuum: it is part of a cultural context. In the past, Thai traditional art absorbed influences from the cultures of neighbouring countries, and the masterworks were often the product of a mix of cultures. So it is today. Cultural interactions create new experiences and ideas. Cultural diversity is the lifeblood of cultural growth. Sometimes outside influences come along with a dominating ideology with economic pressure or with restrictions on autonomy. Historically Thai culture and Thai individuals have been known for their flexibility and ability to adapt. Such flexibility has enabled us to deal with outside trends and influences. If the current of outside influences runs strong, we tend to show acceptance and patience rather than strong reaction in our society. Such ways of coping have been recognised since the time of King Rama IV.

Our culture enjoys extraordinary wealth in art, culture, and resources, both in physical and spiritual terms. We are seen as a fortunate country in many ways. Nevertheless, our rich heritage is under constant threat, both physically and spiritually, and the public must be made aware of this dangerous and lasting damage.

Three artists, three passages to Lanna

We opened this essay with the phrase, “Thailand is not Bangkok.” The phrase applies to Thai contemporary art as well. The Office of the National Culture Commission (ONCC) recognises regional differences in Thai contemporary art and has provided an opportunity for three artists from the North to exhibit their works in Bangkok at the Thailand Cultural Center. The artists are Inson Wongsam, Wattana Wattanapun, and Surasit Saokong.

The ONCC has also commissioned the three artists to set up a team to design a Cultural Park to commemorate the King's eightieth birthday on December 5, 2007. Many pieces of sculpture will be installed in the park surrounding the commemoration building, which will be constructed on ten rai near San Kamphaeng on the eastern bank of Mae Poo Kha Creek. Contemporary artists in Lanna and other parts of the country in the fields of sculpture, painting, and architecture have met to brainstorm the general theme and then to create their own artwork to honour the King. The general design is complete and the individual artists are now creating their work.

Inson Wongsam

Inson was born in Pasang, Lamphun. He is a senior artist, respected by all artists and all people interested in Thai art. He was designated National Artist in the field of visual art (sculpture) by the ONCC in 1999.

Decades ago Inson spent two years traveling from Bangkok to Rome on a Lambretta scooter. Along the way he created artworks and experienced dozens of cultures before finally returning to his home in Pasang, where he has lived ever since.

Most of Inson's work consists of sculpture although he has created some woodcut prints and silk batik. The forty pieces in this exhibition are among his latest woodcut prints. Some were shown in France last August. The works are in black and white and were inspired by Thai poems and proverbs.

Inson's works constantly, and his art is constantly evolving.

Wattana Wattanapun

Wattana was born in Nakorn Prathom province. He graduated from Silapakorn University seven years after Inson. Wattana taught for many years at Chiang Mai University and also spent many years in the US studying and teaching.

He has also taught in Canada. He has been a visiting professor in many colleges, universities, and art institutes in North America. He has received numerous awards and prizes in art competitions in the US. Traveling and living in other cultures has influenced Wattana’s art and enhanced his appreciation of his own culture.

Wattana’s works can be considered paintings though he uses diverse techniques and materials. Wattana has studied patterns in textiles, painting on bamboo and wood, and the technique of squeezing pigment through a tube, which has been practised in India, Burma, Indonesia, and Thalland in the past. Wattana has adapted these patterns and techniques to his aesthetic goals.

His work expresses his passionate ideas about culture, politics and its effect on individuals, the treatment of ethnic minorities, and exploitation. Prominent themes are gentleness, vulnerability, powerlessness, and abuse, either hidden or overt. These themes are literally woven into patterns, fabrics, and bamboo. Many of the works express ambivalence: on the one hand, one sees beauty and aesthetically pleasing forms; on the other, one cannot completely hide the desire to consume and enjoy that which is beautiful, even when the consequences may cause harm.

Wattana’s work with the ONCC includes participating with the committee to review proposals for research projects on art and culture in the North. He also heads the team to design the cultural park to commemorate the King’s eightieh birthday in San Kamphaeng.

Wattana is a freelance artist residing on Wat Umong Lane in Chiang Mai.

Surasit Saokong

Surasit was born in Roi-et. He graduated six years after Wattana. He is currently a tenured assistant professor of art at Rajamongala Institute of Technology, Lanna. Many of his students have become well known. He won the National Outstanding Teacher award.

Surasit has developed great skill in realistic painting. He has won many national awards and was recognised as a Master of Thailand by Fine Art magazine, July 2006.

Much of Surasit's work is characterised by serenity. The light and shadow in his large oil paintings draw observers into meditative states. His painting of a Lanna temple scene is an idealistic impression. Though such images no longer exist, his work reminds viewers that once it was “just like that.”

In a painting titled “Serenity 2006”, Surasit wrote: “Glorious light at certain spots in the painting leads the viewers’ eyes through the door, which is carved into fine golden patterns, to the well-lighted mural painting of the epic story of Lord Buddha’s birth.

“Light illuminates the delicacy of the skin on the statue of Lord Buddha. The architectural details appear clean, free of dust or deterioration that might distract our eyes. Viewers see graceful Lanna patterns, reflecting light as if it were wisdom itself, by which dark desire is eliminated and suffering finally ends.

“It is the peace that leaves behind anger, attachment, and greed: it is the peace of happiness based on wisdom. Light and shadow do not sharply contrast but are balanced, allowing a subtle harmony to emerge, leading one away to a boundless expanse, to a state of bright stillness where our search can finally cease, where existence has passed through and beyond time.”

Insiders and outsiders

Of the three artists in this exhibition, Inson is the only one who was born in Lanna. He spent several years overseas, however, acquiring some of the distance has allowed him to look at his own culture with an outsider’s eyes.

Wattana and Surasit are outsiders in that they were not born in Lanna, though they have each lived in the North for more than thirty years. They have put down roots here, and have spent years watching, listening, and studying this region for which they feel such affection and admiration. Their work has some of the objectivity of outsiders who have nonetheless come to think of Lanna as home for much of their adult lives.

All three artists have attempted to communicate aspects of Lanna through different points of view as well as different modes and techniques. That said, the works in this exhibition are all unified in several ways — first by the artists’ deep affection for Lanna, their home. The works are also tied together by their artistic integrity, by the skill and talent exhibited in the works, and the obvious passion the artists have for what they want to communicate. Viewers who see this exhibition can expect to see a rich manifestation of the Thailand that is not Bangkok.

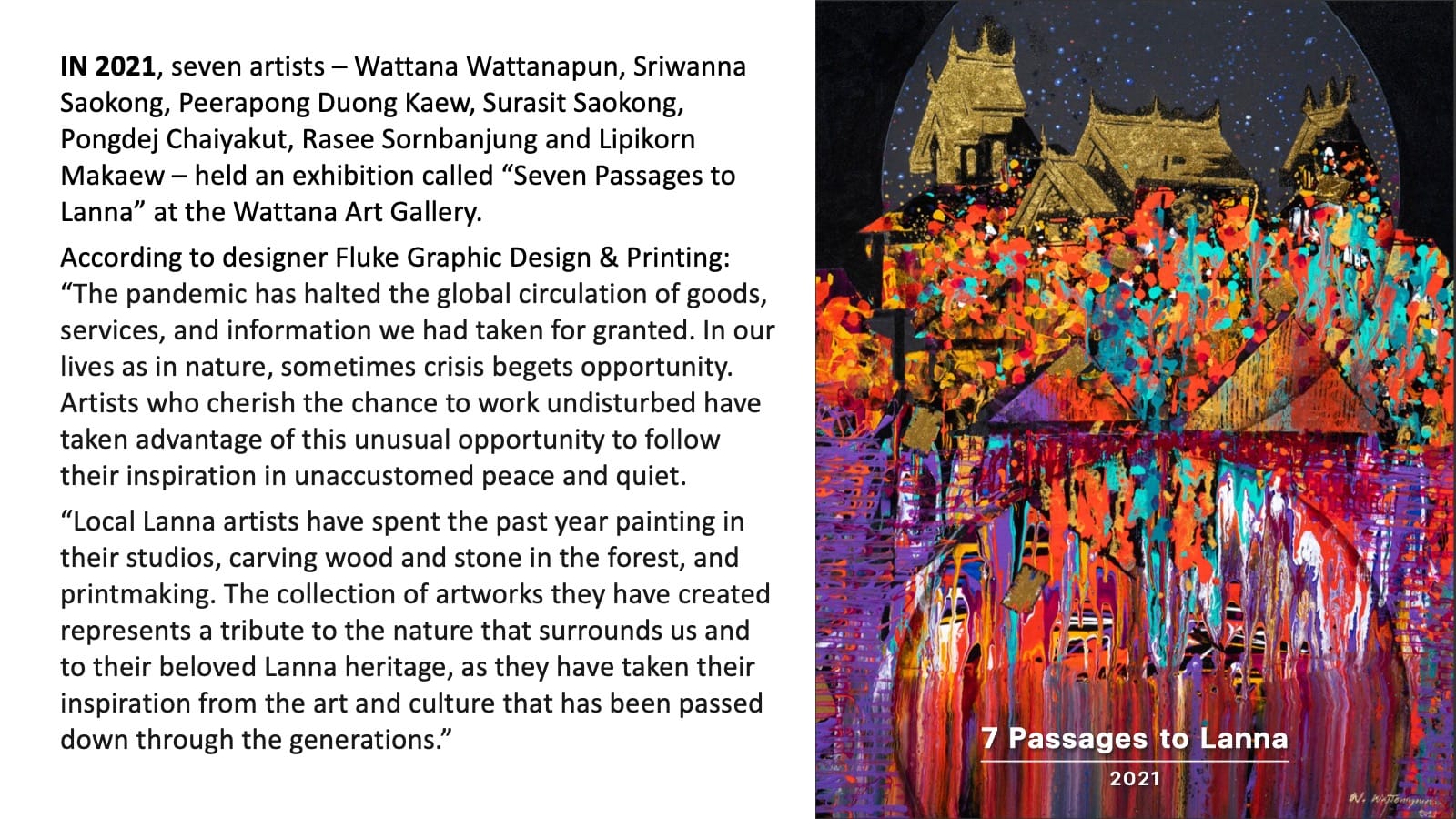

Seven Passages to Lanna

Click here to read and download the eBook. And here to view a report on its launch.

Art & Storytelling

On the evening of January 7th, I made a presentation on “Art & Storytelling” to many of Wattana’s friends and former colleagues from the University of Chiang Mai. There was a good exchange of ideas. In addition, we had great food, drinks and music. It was a great way to talk about art.